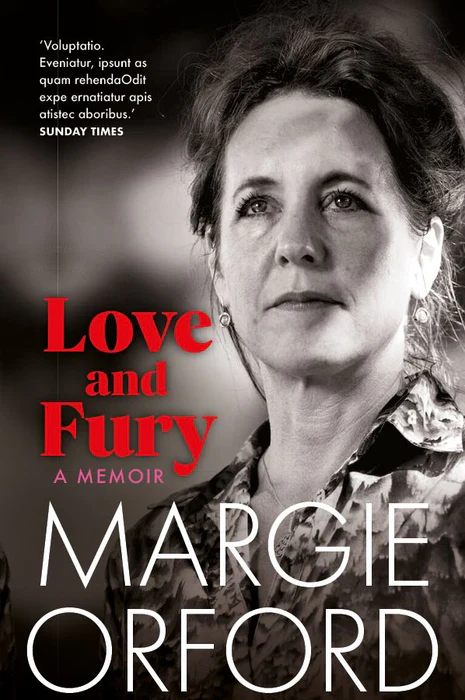

Author Margie Orford takes readers to a challenging, vulnerable, beautiful place in her memoir, Love And Fury

Your fiction writing reflects many of your views about society’s treatment of women, but this book opens up everything about you at a vastly more vulnerable level. How liberating or revelatory was it to dig that deep?

Margie Orford: It was really difficult, but liberating in all sorts of interesting ways. There was a ’60s term, ‘women’s liberation’, but it wasn’t always about freedom and liberty in the sense of being able to be a true person or the person you wanted to be. This book was revelatory to me. I started writing it in 2018, as I couldn’t sell the manuscript for a book I’d finished, called Eye Of The Beholder. My publisher said a memoir would be a good idea, as that kind of thing was popular at the time. I realised I’d kind of split off from myself in the serial writing of violence against women.

Some autobiographies are unsatisfactory, dealing only in the greatest hits of someone’s life. For me, it was difficult determining what to write. I did an archaeological study of myself and winnowed out what kept coming up for me. That part included family history, which was not relevant. My editors were helpful, showing where the story came alive. Working through it, I realised – which I hadn’t before – that my novels might reflect my own experiences. I wrote to know, to make it come alive by being absolutely specific about what happened.

It didn’t feel like a brave thing to do. It was more about putting together the motorbike of my life that had been taken apart and left all over a workbench. But what I understood about violence based on dominance and submission was that it becomes the victim’s responsibility to keep the secret of what happened. The abuser is shameless – you carry it. We’re conditioned to not tell tales, but kids must rather be taught to not keep such secrets. The shame must be given back to the perpetrator: it’s not about courage; it’s just sensible.

In the book, you deal with a number of institutions in terms of how they failed or did not help you as a woman, as a wife and mother, and as a writer.

Margie Orford: You have no idea when you’re young about how to be yourself. The roles and ideals of wife, mother, and so on are split apart from you – it’s a mad feeling. A lot of my maturing was undoing that. I sought psychological help when I was 19. I was depressed. A student psychologist didn’t help. If I’d been helped properly then, it would have made my life completely different. Today, we seek immediate help for mental health, as if it was a cold. We know it’s important.

Political changes also matter. South Africa under apartheid drove people insane. It was gaslighting at a macro level; both public and private madness. The backlash against feminism in the USA at the moment is a marker of how powerful changes have been and how much they were needed.

Ultimately, you battled your way to a space where you are highly respected for being you – an intellectual, activist, and more. How satisfying is that? Is there more to come?

Margie Orford: I’m busy writing another novel. I don’t know if there’ll be more memoirs. You can’t tell different truths in different ways. But one of the amazing things about the memoir was having the joy of my marriage returned to me. After the break-up, I only remembered loss. Memoir involves dealing with people you profoundly care about, so there is a moral responsibility to not beat the reader over the head with your trauma, but rather to take them through that and what they identify with in it to a place where the subject – me, in this case – makes it to a better place. I tell myself to look at myself in the same empathetic way as I looked at the victims in my fiction books.

Speaking or writing about the sexual abuse you suffered: what is the importance of doing so in the context of your personal activism as well as in the context of the whole gender-based violence crisis in South Africa and elsewhere?

Margie Orford: Anything we can do to reduce the long-term psychological damage to people is immensely valuable. If you are a sexual assault survivor, it takes up an enormous amount of energy and time in your life. Had I figured that out earlier, it would have saved me a lot of time and pain. Multiply yourself by all the people stuff like this has happened to and you start to understand the difference that knowledge makes. I think if I know something, I must share or use it. Patriarchy – or anything dictatorial, for that matter – is a huge waste of time. It outraged me, what happened to me. I want more space for my daughters in this area, as well as for liberated men who have fewer heart attacks because they see that they don’t need to be macho.

Text | Bruce Dennill Photography | Supplied

Love And Fury by Margie Orford, published by Jonathan Ball, is available now. For more information, go to jonathanball.co.za.